ProMed

New member

from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/576784

An Unusual Case of Gynecomastia Associated With Soy Product Consumption

Jorge Martinez, MD; Jack E. Lewi, MD, FACP, FACE

Endocr Pract. 2008;14(4):415-418. ©2008 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

Posted 08/01/2008

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Objective: To document a case of gynecomastia related to ingestion of soy products and review the literature.

Methods: We present the clinical course of a man with gynecomastia in relation to ingestion of 2 different soy products and review related literature.

Results: A 60-year-old man was referred to the endocrinology clinic for evaluation of bilateral gynecomastia of 6 months' duration. He reported erectile dysfunction and decreased libido. On further review of systems, he reported no changes in testicular size, no history of testicular trauma, no sexually transmitted diseases, no headaches, no visual changes, and no change in muscular mass or strength. Initial laboratory assessment showed estrone and estradiol concentrations to be 4-fold increased above the upper limit of the reference range. Subsequent findings from testicular ultrasonography; computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and positron emission tomography were normal. Because of the normal findings from the imaging evaluation, the patient was interviewed again, and he described a daily intake of 3 quarts of soy milk. After he discontinued drinking soy milk, his breast tenderness resolved and his estradiol concentration slowly returned to normal.

Conclusions: This is a very unusual case of gynecomastia related to ingestion of soy products. Health care providers should thoroughly review patients' dietary habits to possibly reveal the etiology of medical conditions.

Introduction

Gynecomastia (breast enlargement in male individuals) is relatively common in male infants, pubertal boys, and elderly men.[1] Although it is usually symmetric, it can be unilateral. Careful physical examination along with ultrasonography or radiographs can help distinguish gynecomastia from excess adipose. Gynecomastia can be due to relative estrogen excess such as in the settings of testicular failure or androgen resistance, and it can also be caused by absolute high levels of estrogen due to testicular tumors, bronchogenic carcinoma, adrenal disease, thyrotoxicosis, or liver disease. Many drugs can cause gynecomastia, including drugs that decrease testosterone synthesis such as ketoconazole, metronidazole, or cytotoxic agents and drugs that decrease testosterone action such as marijuana, cimetidine, flutamide, and spironolactone. Furthermore, some drugs such as isoniazid, penicillamine, calcium channel blockers, and central nervous system agents (including diazepam, tricyclic antidepressants, reserpine, phenytoin, and amphetamines)[2] can cause gynecomastia via an unknown mechanism of action. Gynecomastia has also been linked to tea tree oil and lavender oil.[3] Phytoestrogens, a component of soy products, have estrogen-like properties, and in large amounts they can lead to gynecomastia.[4] We describe a case of gynecomastia related to consumption of large amounts of soy products.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man was referred to the endocrinology clinic for evaluation of bilateral gynecomastia of 6 months' duration. He had noted decreased libido and erectile dysfunction during the previous 6 months, which were new symptoms. He had no change in shaving habits and no change in the size of his testes. He had gained a few pounds over the 6-month period, but he reported that weight gain was not unusual for him during the cooler months of the year, and his body mass index remained around 21 kg/m2. He noted tenderness around both of his nipples, but no breast discharge. He had no history of testicular trauma, testicular inflammation, or sexually transmitted disease. He had no headaches, no visual field changes, and no change in muscle mass or strength. He reported being the biological father of a 34-year-old son.

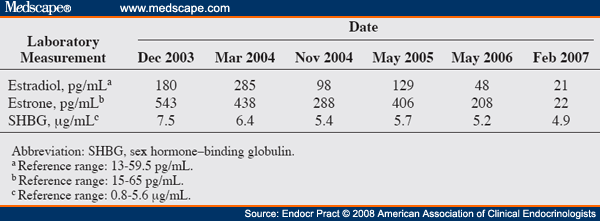

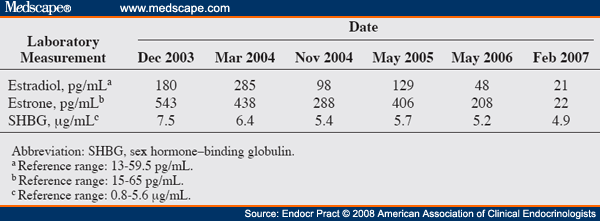

On physical examination, he had normal genitalia and bilateral, tender gynecomastia. He was noted to have normal concentrations of β-human chorionic gonadotropin, prolactin, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and total and free testosterone. Thyroid function test results, renal function, and liver function were normal. However, his estradiol concentration was 180 pg/mL (reference range, 13-59 pg/mL) and his estrone concentration was 543 pg/mL (reference range, 15-65 pg/mL), with a normal androstenedione concentration and slightly low dehydroepiandrosterone concentration. The estradiol and testosterone levels were calculated values by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. His sex hormone–binding globulin concentrations are listed in Table 1 . He had normal findings from ultrasonography of the testes; computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and positron emission tomography. Repeated laboratory testing revealed normal concentrations of free and total testosterone and elevated concentrations of estradiol, estrone, and free estradiol. When discussing dietary history, the patient revealed he was drinking 3 quarts of soy milk per day because of lactose intolerance. He was asked to abstain from ingesting soy milk and other soy products. His estradiol and estrone concentrations began falling to near normal levels over the next several months, but then started climbing again. Upon further interviews, the patient described substituting another nonlactose product for the soy milk and did not read that it contained soy as a major ingredient. After discontinuing the nonlactose soy product, his estradiol and estrone levels decreased to the reference range and have remained normal ( Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between estrogen concentrations and soy product consumption in the study patient over a period of 3 years.

Discussion

The evaluation of gynecomastia must include a thorough history and physical examination, including testicular examination.[5] Baseline laboratory tests should include a comprehensive chemistry assessment (including liver function tests and renal panel); thyroid function tests; testosterone panel; and measurement of β-human chorionic gonadotropin, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and estradiol. Ultrasonography of the testes is recommended in cases of high β-human chorionic gonadotropin and/or high estradiol concentrations. If ultrasonography findings of the testes are normal, abdominal and chest computed tomography should be performed to look for bronchogenic carcinoma or germ cell tumors. If computed tomography findings are also normal, the differential diagnosis includes high aromatase activity producing high endogenous sources of estrogen vs other exogenous sources of estrogen.[6] Conversion of androstenedione and testosterone via aromatase produces most of the circulating estradiol and estrone in men. Testosterone, estradiol, and estrone are bound to sex hormone–binding globulin in circulation. Because testosterone has a higher affinity for sex hormone–binding globulin, increases in sex hormone–binding globulin will favor more free estradiol and estrone than testosterone.[7]

Gynecomastia has been reported with ingestion of herbal supplements containing phytoestrogen.[4] Soy milk and soy protein have been extensively studied for the last 15 years for their possible beneficial effects in human health including decreased cholesterol levels,[8,9] decreased prostate cancer[10] and breast cancer[11] incidence, decreased menopausal symptoms,[12,13] and increased bone density.[14,15] It is very well documented that soy milk contains phytoestrogens. More specifically, the soy milk phytoestrogens are known as the isoflavones genistein and daidzein, which are structurally and functionally similar to 17 β-estradiol, but with weaker bioactivity than estradiol[16] (Figure 2). Ingested isoflavones undergo biotransformation by the intestinal microflora followed by absorption and enterohepatic recycling, which can result in high circulating concentrations.[17] This is one reason why the estradiol levels were delayed in returning to the reference range in the described patient. There is much variability in absorption of isoflavones from one individual to another.[18] It is possible that large amounts of isoflavones could explain the increase in estradiol and estrone concentrations and could have caused the gynecomastia in our patient. Soy isoflavones probably interfere with the CYP enzymes that assist in the metabolism of estrogen.[19] The usual amount of phytoestrogen in a cup of soy milk is 25 mg. Our patient was drinking 3 quarts of soy milk a day, which is the equivalent of taking 361 mg of isoflavones a day.

Figure 2.

Phytoestrogens (isoflavones) genistein and daidzein, structurally and functionally similar to 17 β-estradiol and estrone, are less bioactive.

The treatment of gynecomastia is predicated on the underlying cause. Treatment of idiopathic gynecomastia is difficult, but tamoxifen, clomiphene citrate, and testolactone have been used with some success.[20] Surgical removal of the breast tissue can be done once the underlying cause has been treated.[21] The longer the gynecomastia is present, the chance of resolution without surgical reduction decreases because of fibrotic tissue changes that occur.[22]

Conclusion

Soy milk is not considered a medicinal or herbal supplement. In this case, the patient was drinking soy milk because of lactose intolerance. With a myriad of dietary supplements and choices, it is important for health care providers to thoroughly review patients' dietary habits to possibly reveal the etiology of unusual medical conditions.

Table 1. Laboratory Test Results of the Study Patient

References

Narula HS, Carlson HE. Gynecomastia. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2007;36:497-519.

Bhasin S. Gynecomastia. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed, S, Polonsky KS, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 2003: 741-746.

Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach K, Block CA. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:479-485.

Goh SY, Loh KC. Gynaecomastia and the herbal tonic "Dong Quai." Singapore Med J. 2001;42:115-116.

Cakan N, Kamat D. Gynecomastia: evaluation and treatment recommendations for primary care providers. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46:487-490.

Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328: 490-495.

de Ronde W, van der Schouw YT, Muller M, et al. Associations of sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) with non-SHBG-bound levels of testosterone and estradiol in independently living men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:157-162.

Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Cook-Newell ME. Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:276-282.

Somekawa Y, Chiguchi M, Ishibashi T, Aso T. Soy intake related to menopausal symptoms, serum lipids, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Japanese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:109-115.

Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Fraser GE. Does high soy milk intake reduce prostate cancer incidence? The Adventist Health Study (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1988;9:553-557.

Martínez ME, Thomson CA, Smith-Warner SA. Soy and breast cancer: the controversy continues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:430-431.

Crisafulli A, Marini H, Bitto A, et al. Effects of genistein on hot flashes in early postmenopausal women: a randomized, double-blind EPT- and placebo-controlled study. Menopause. 2004;11:400-404.

Tham DM, Gardner CD, Haskell WL. Clinical review 97: Potential health benefits of dietary phytoestrogens: a review of the clinical, epidemiological, and mechanistic evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2223-2235.

Marini H, Minutoli L, Polito F, et al. Effects of the phytoestrogen genistein on bone metabolism in osteopenic postmenopausal women: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:839-847.

Lydeking-Olsen E, Beck-Jensen JE, Setchell KD, Holm-Jensen T. Soymilk or progesterone for prevention of bone loss--a 2 year randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2004;43:246-257.

Kostelac D, Rechkemmer G, Briviba K. Phytoestrogens modulate binding response of estrogen receptors alpha and beta to the estrogen response element. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7632-7635.

Setchell KD. Phytoestrogens: the biochemistry, physiology, and implications for human health of soy isoflavones. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(6 Suppl):1333-1346.

Atkinson C, Frankenfeld CL, Lampe JW. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone daidzein: exploring the relevance to human health. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2005;230:155-170.

Xu X, Duncan AM, Merz BE, Kurzer MS. Effects of soy isoflavones on estrogen and phytoestrogen metabolism in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1101-1108.

Braunstein GD. Aromatase and gynecomastia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:315-324.

Wiesman IM, Lehman JA Jr, Parker MG, Tantri MD, Wagner DS, Pedersen JC. Gynecomastia: an outcome analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:97-101.

Andersen JA, Gram JB. Gynecomasty: histological aspects in a surgical material. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [A]. 1982;90:185-190.

Reprint Address

Dr. Jack E. Lewi, Endocrinology Service/SGOME, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 2200 Berquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; Email: [email protected]

Jorge Martinez, MD1 and Jack E. Lewi, MD, FACP, FACE2

1Department of Medicine, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas

2Endocrinology Service, San Antonio Military Medical Center, San Antonio, Texas

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

An Unusual Case of Gynecomastia Associated With Soy Product Consumption

Jorge Martinez, MD; Jack E. Lewi, MD, FACP, FACE

Endocr Pract. 2008;14(4):415-418. ©2008 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

Posted 08/01/2008

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Objective: To document a case of gynecomastia related to ingestion of soy products and review the literature.

Methods: We present the clinical course of a man with gynecomastia in relation to ingestion of 2 different soy products and review related literature.

Results: A 60-year-old man was referred to the endocrinology clinic for evaluation of bilateral gynecomastia of 6 months' duration. He reported erectile dysfunction and decreased libido. On further review of systems, he reported no changes in testicular size, no history of testicular trauma, no sexually transmitted diseases, no headaches, no visual changes, and no change in muscular mass or strength. Initial laboratory assessment showed estrone and estradiol concentrations to be 4-fold increased above the upper limit of the reference range. Subsequent findings from testicular ultrasonography; computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and positron emission tomography were normal. Because of the normal findings from the imaging evaluation, the patient was interviewed again, and he described a daily intake of 3 quarts of soy milk. After he discontinued drinking soy milk, his breast tenderness resolved and his estradiol concentration slowly returned to normal.

Conclusions: This is a very unusual case of gynecomastia related to ingestion of soy products. Health care providers should thoroughly review patients' dietary habits to possibly reveal the etiology of medical conditions.

Introduction

Gynecomastia (breast enlargement in male individuals) is relatively common in male infants, pubertal boys, and elderly men.[1] Although it is usually symmetric, it can be unilateral. Careful physical examination along with ultrasonography or radiographs can help distinguish gynecomastia from excess adipose. Gynecomastia can be due to relative estrogen excess such as in the settings of testicular failure or androgen resistance, and it can also be caused by absolute high levels of estrogen due to testicular tumors, bronchogenic carcinoma, adrenal disease, thyrotoxicosis, or liver disease. Many drugs can cause gynecomastia, including drugs that decrease testosterone synthesis such as ketoconazole, metronidazole, or cytotoxic agents and drugs that decrease testosterone action such as marijuana, cimetidine, flutamide, and spironolactone. Furthermore, some drugs such as isoniazid, penicillamine, calcium channel blockers, and central nervous system agents (including diazepam, tricyclic antidepressants, reserpine, phenytoin, and amphetamines)[2] can cause gynecomastia via an unknown mechanism of action. Gynecomastia has also been linked to tea tree oil and lavender oil.[3] Phytoestrogens, a component of soy products, have estrogen-like properties, and in large amounts they can lead to gynecomastia.[4] We describe a case of gynecomastia related to consumption of large amounts of soy products.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man was referred to the endocrinology clinic for evaluation of bilateral gynecomastia of 6 months' duration. He had noted decreased libido and erectile dysfunction during the previous 6 months, which were new symptoms. He had no change in shaving habits and no change in the size of his testes. He had gained a few pounds over the 6-month period, but he reported that weight gain was not unusual for him during the cooler months of the year, and his body mass index remained around 21 kg/m2. He noted tenderness around both of his nipples, but no breast discharge. He had no history of testicular trauma, testicular inflammation, or sexually transmitted disease. He had no headaches, no visual field changes, and no change in muscle mass or strength. He reported being the biological father of a 34-year-old son.

On physical examination, he had normal genitalia and bilateral, tender gynecomastia. He was noted to have normal concentrations of β-human chorionic gonadotropin, prolactin, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and total and free testosterone. Thyroid function test results, renal function, and liver function were normal. However, his estradiol concentration was 180 pg/mL (reference range, 13-59 pg/mL) and his estrone concentration was 543 pg/mL (reference range, 15-65 pg/mL), with a normal androstenedione concentration and slightly low dehydroepiandrosterone concentration. The estradiol and testosterone levels were calculated values by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. His sex hormone–binding globulin concentrations are listed in Table 1 . He had normal findings from ultrasonography of the testes; computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and positron emission tomography. Repeated laboratory testing revealed normal concentrations of free and total testosterone and elevated concentrations of estradiol, estrone, and free estradiol. When discussing dietary history, the patient revealed he was drinking 3 quarts of soy milk per day because of lactose intolerance. He was asked to abstain from ingesting soy milk and other soy products. His estradiol and estrone concentrations began falling to near normal levels over the next several months, but then started climbing again. Upon further interviews, the patient described substituting another nonlactose product for the soy milk and did not read that it contained soy as a major ingredient. After discontinuing the nonlactose soy product, his estradiol and estrone levels decreased to the reference range and have remained normal ( Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between estrogen concentrations and soy product consumption in the study patient over a period of 3 years.

Discussion

The evaluation of gynecomastia must include a thorough history and physical examination, including testicular examination.[5] Baseline laboratory tests should include a comprehensive chemistry assessment (including liver function tests and renal panel); thyroid function tests; testosterone panel; and measurement of β-human chorionic gonadotropin, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and estradiol. Ultrasonography of the testes is recommended in cases of high β-human chorionic gonadotropin and/or high estradiol concentrations. If ultrasonography findings of the testes are normal, abdominal and chest computed tomography should be performed to look for bronchogenic carcinoma or germ cell tumors. If computed tomography findings are also normal, the differential diagnosis includes high aromatase activity producing high endogenous sources of estrogen vs other exogenous sources of estrogen.[6] Conversion of androstenedione and testosterone via aromatase produces most of the circulating estradiol and estrone in men. Testosterone, estradiol, and estrone are bound to sex hormone–binding globulin in circulation. Because testosterone has a higher affinity for sex hormone–binding globulin, increases in sex hormone–binding globulin will favor more free estradiol and estrone than testosterone.[7]

Gynecomastia has been reported with ingestion of herbal supplements containing phytoestrogen.[4] Soy milk and soy protein have been extensively studied for the last 15 years for their possible beneficial effects in human health including decreased cholesterol levels,[8,9] decreased prostate cancer[10] and breast cancer[11] incidence, decreased menopausal symptoms,[12,13] and increased bone density.[14,15] It is very well documented that soy milk contains phytoestrogens. More specifically, the soy milk phytoestrogens are known as the isoflavones genistein and daidzein, which are structurally and functionally similar to 17 β-estradiol, but with weaker bioactivity than estradiol[16] (Figure 2). Ingested isoflavones undergo biotransformation by the intestinal microflora followed by absorption and enterohepatic recycling, which can result in high circulating concentrations.[17] This is one reason why the estradiol levels were delayed in returning to the reference range in the described patient. There is much variability in absorption of isoflavones from one individual to another.[18] It is possible that large amounts of isoflavones could explain the increase in estradiol and estrone concentrations and could have caused the gynecomastia in our patient. Soy isoflavones probably interfere with the CYP enzymes that assist in the metabolism of estrogen.[19] The usual amount of phytoestrogen in a cup of soy milk is 25 mg. Our patient was drinking 3 quarts of soy milk a day, which is the equivalent of taking 361 mg of isoflavones a day.

Figure 2.

Phytoestrogens (isoflavones) genistein and daidzein, structurally and functionally similar to 17 β-estradiol and estrone, are less bioactive.

The treatment of gynecomastia is predicated on the underlying cause. Treatment of idiopathic gynecomastia is difficult, but tamoxifen, clomiphene citrate, and testolactone have been used with some success.[20] Surgical removal of the breast tissue can be done once the underlying cause has been treated.[21] The longer the gynecomastia is present, the chance of resolution without surgical reduction decreases because of fibrotic tissue changes that occur.[22]

Conclusion

Soy milk is not considered a medicinal or herbal supplement. In this case, the patient was drinking soy milk because of lactose intolerance. With a myriad of dietary supplements and choices, it is important for health care providers to thoroughly review patients' dietary habits to possibly reveal the etiology of unusual medical conditions.

Table 1. Laboratory Test Results of the Study Patient

References

Narula HS, Carlson HE. Gynecomastia. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2007;36:497-519.

Bhasin S. Gynecomastia. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed, S, Polonsky KS, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 2003: 741-746.

Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach K, Block CA. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:479-485.

Goh SY, Loh KC. Gynaecomastia and the herbal tonic "Dong Quai." Singapore Med J. 2001;42:115-116.

Cakan N, Kamat D. Gynecomastia: evaluation and treatment recommendations for primary care providers. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46:487-490.

Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328: 490-495.

de Ronde W, van der Schouw YT, Muller M, et al. Associations of sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) with non-SHBG-bound levels of testosterone and estradiol in independently living men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:157-162.

Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Cook-Newell ME. Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:276-282.

Somekawa Y, Chiguchi M, Ishibashi T, Aso T. Soy intake related to menopausal symptoms, serum lipids, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Japanese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:109-115.

Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Fraser GE. Does high soy milk intake reduce prostate cancer incidence? The Adventist Health Study (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1988;9:553-557.

Martínez ME, Thomson CA, Smith-Warner SA. Soy and breast cancer: the controversy continues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:430-431.

Crisafulli A, Marini H, Bitto A, et al. Effects of genistein on hot flashes in early postmenopausal women: a randomized, double-blind EPT- and placebo-controlled study. Menopause. 2004;11:400-404.

Tham DM, Gardner CD, Haskell WL. Clinical review 97: Potential health benefits of dietary phytoestrogens: a review of the clinical, epidemiological, and mechanistic evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2223-2235.

Marini H, Minutoli L, Polito F, et al. Effects of the phytoestrogen genistein on bone metabolism in osteopenic postmenopausal women: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:839-847.

Lydeking-Olsen E, Beck-Jensen JE, Setchell KD, Holm-Jensen T. Soymilk or progesterone for prevention of bone loss--a 2 year randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2004;43:246-257.

Kostelac D, Rechkemmer G, Briviba K. Phytoestrogens modulate binding response of estrogen receptors alpha and beta to the estrogen response element. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7632-7635.

Setchell KD. Phytoestrogens: the biochemistry, physiology, and implications for human health of soy isoflavones. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(6 Suppl):1333-1346.

Atkinson C, Frankenfeld CL, Lampe JW. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone daidzein: exploring the relevance to human health. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2005;230:155-170.

Xu X, Duncan AM, Merz BE, Kurzer MS. Effects of soy isoflavones on estrogen and phytoestrogen metabolism in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1101-1108.

Braunstein GD. Aromatase and gynecomastia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:315-324.

Wiesman IM, Lehman JA Jr, Parker MG, Tantri MD, Wagner DS, Pedersen JC. Gynecomastia: an outcome analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:97-101.

Andersen JA, Gram JB. Gynecomasty: histological aspects in a surgical material. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [A]. 1982;90:185-190.

Reprint Address

Dr. Jack E. Lewi, Endocrinology Service/SGOME, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 2200 Berquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; Email: [email protected]

Jorge Martinez, MD1 and Jack E. Lewi, MD, FACP, FACE2

1Department of Medicine, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas

2Endocrinology Service, San Antonio Military Medical Center, San Antonio, Texas

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Please Scroll Down to See Forums Below

Please Scroll Down to See Forums Below